I've been reading

True History of the Kelly Gang, the Booker prize-winning novel by the Aussie Peter Carey. I enjoyed it much more than his

Jack Maggs.

History is told in the delightful Ozzie brogue of the famed outlaw. It falls into that category of fictional account of a historical personage (see Coover,

The Public Burning; DeLillo,

Libra). Of course we know it's fiction and not history, but we suspend our disbelief, immerse ourselves, and imagine we are seeing events through the

spongeworthy eyes of a barely literate, biased observer/

flaneur.

I am put in mind of a group of contemporary novels in the tradition of

Crime and Punishment: Vladimir Nabokov's classic and controversial

Lolita (1955), John Fowles's

The Collector (1963), Evan S. Connell's

The Diary of a Rapist (1966), John Banville's Booker-nominated

The Book of Evidence (1989), and James Lasdun's

The Horned Man (2002). All are told in first person—though

The Collector has a middle section told from a POV other than the protagonist. If you need a cubby to put them in, you could call them "psychological realism X" (for X-treme), but I don't read books because they fit into some convenient category. I read them because they're well-written. And this group is superb.

Everyone knows Humbert Humbert's melancholy confessional of the stalking, gaining, and eventual losing of Lolita.

The Collector, Fowles's first novel, is the story of a methodical, lottery-winning butterfly collector who connives to upgrade his quarry to include a beautiful young art student and possibly others.

Diary follows an obscure civil servant's descent into the depths of resentment, self-loathing, misanthropy, and ultimately criminality.

The Book of Evidence is written as a mocking confessional by the murderous and notoriously unreliable art thief Freddy Montgomery.

The Horned Man, in my opinion the best of a superior lot, drops us behind enemy lines and right smack in the mind of a paranoid, radically alienated professor of gender studies.

None of the protagonists in these five books is likable; you wouldn't want to have a beer with any of these murderers, kidnappers, rapists, thieves, or madmen. You can't identify with them—unless you are prepared to delve into your own dark places (and that, after all, is the point, the challenge of such books). They are complex characters with strange motivations and bizarre rationalizations; none is quite forgettable. The books are profound. Each in its own way is concerned—and here is where we escape the pigeon holes and easy labels—with beauty and the possibility of transformation. Excerpts:

Nabokov:

"You have to be an artist and a madman, a creature of infinite melancholy, with a bubble of hot poison in your subtle spine (oh, how you have to cringe and hide!), in order to discern at once, by ineffable signs—the slightly feline outline of a cheekbone, the slenderness of a downy limb, and other indices which despair and shame and tears of tenderness forbid me to tabulate—the little deadly demon among the wholesome children; she stands unrecognized by them and unconscious herself of her fantastic power." (19)

Fowles:

"Seeing her always made me feel like I was catching a rarity, going up to it very careful, heart-in-mouth as they say. A Pale Clouded Yellow, for instance. I always thought of her like that, I mean words like elusive and sporadic, and very refined—not like the other ones, even the pretty ones. More for the real connoisseur." (3)

Connell (if you don't know him, you should):

"To the mirror once again. Why can't I break this habit? I look for my face so often, think that my significance ought to be reflected but there's not much change. I note only that secrecy goes well with my appearance. Rigid pose. I can't say that I'm graceful, but my eyes are black & full of interesting lights. Also I do think that as I've matured my features have acquired—umm, what? Am I more impressive? I've noticed that others stop talking when I approach. And yet few learn from a face what's happening in the deeps of the soul. My perception must be singular, not much escapes me. However as I think about that it's not surprising—no, not at all. Why, compared to me most men are as simple as cattle. All that troubles me, in fact, is that I'm not able to feel certain emotions, ordinary states that others enjoy. Familiar feelings I used to know. Happiness & sorrow. I've lost the power to absorb them.

... "So ends the month & leaves a taste of copper on my tongue." (239-40)

Banville:

"What did I feel? Remorse, grief, a terrible—no no no, I won't lie. I can't remember feeling anything, except that sense of strangeness, of being in a place I knew but did not recognise. When I got out of the car I was giddy, and had to lean on the door for a moment with my eyes shut tight. My jacket was bloodstained, I wriggled out of it and flung it into the stunted bushes—they never found it, I can't think why. I remembered the pullover in the boot, and put it on. It smelled of fish and sweat an axle-grease. I picked up the hangman's hank of rope and threw that away too. Then I lifted out the picture and walked with it to where there was a sagging barbed-wire fence and a ditch with a trickle of water at the bottom, and there I dumped it. What was I thinking of, I don't know. Perhaps it was a gesture of renunciation or something. Renunciation! How do I dare use such words. The woman with the gloves [the subject of the stolen portrait] gave me a last, dismissive stare. She had expected no better of me. I went back to the car, trying not to look at it, the smeared windows. Something was falling on me: a delicate, silent fall of rain. I looked upwards in the glistening sunlight and saw a cloud directly overhead, the merest smear of grey against the summer blue. I thought: I am not human. Then I turned and walked away." (119)

Lasdun (seriously, get this book; treasure it):

"I was unaware of any nocturnal visitation, human or otherwise, but when I emerged at dawn, bleary and unclean, I realized even before I caught sight of myself in one of Trumilcik's strategically placed mirrors that something truly catastrophic had come to pass.

"Forcing myself to stand still and confront my reflected head, I had the sensation of fainting rapidly through successive layers of consciousness, but without the luxury of passing out.

"A thick, white, hornlike protrusion had grown out of my forehead.

"I knew, of course, that this could not be so; that I was either still asleep and dreaming it, or that the mounting pressure of these past few days had made me suggeistible to the point of hallucination. But this knowledge didn't remotely lessen the terror I felt as I stared at my image in the mirror. Gingerly, I raised my hand to the protrusion, praying that the sense of touch—less given to hysteria, perhaps, than that of sight—would prove the monstrosity an apparition and make it vanish. Unfortunately, it had the opposite effect. The thing felt appallingly real: hard, rock-smooth, and icy cold.

"Though I was no longer in pain, I felt as though I had become extremely ill. Something had shifted in my relationship to my surroundings. Physically, materially, they were unchanged, but in some essential way they seemed to be receding from me, or I from them. It was as though I had switched sides in a train, and what once rushed to meet me had started slipping away. I looked at the furnishings with an odd feeling that I recognized after a moment as yearning. I wasn't so much seeing these ordinary things—the black-stained chairs, the sunflower clock, the pottery mugs, the five- to seven-cup Hot Pot coffeemaker—as yearning for them. I was filled with nostalgia for them as if my world and theirs had already parted company." (182-83)

True History of the Kelly Gang has no such pretensions. It is a well-told, fairly straightforward tale. The protagonist is made sympathetic, unlike those above, by his honest motives (his love of his mother, his wife, and his daughter) and his lack of guile. Though he is a criminal, his side of why he did the notorious things he did has some plausibility given the authenticity and sincerity of his voice—this, of course, is a tribute to Carey's skill. Ned Kelly is not portrayed as mad, but is driven by circumstances further and further into exile from an unjust and corrupt colonial society.

True History has none of the psychological complexity nor transformational beauty—and, indeed, horror—of the other novels. It is, by all mean, a great romp. A ripping good yarn. Epic even. Fully-realized, as they say. A good read; I can highly recommend it. But I will not go back to it again and again. The style is wonderful: there are quite good turns of phrase and the voice is winning. The protagonist is charming and the action is riveting—it keeps you reading. Never fails to entertain. Yet, despite all its skillfully-executed, writerly craft, it is not art.

[For context on this point I refer you to the ongoing discussion raised by our post re: Jill Lepore's comparison of history to fiction in last week's

New Yorker here and over at Dan Green's outstanding blog

The Reading Experience.]

Anybody seen Harvey?

Anybody seen Harvey?

On Strike!

On Strike!

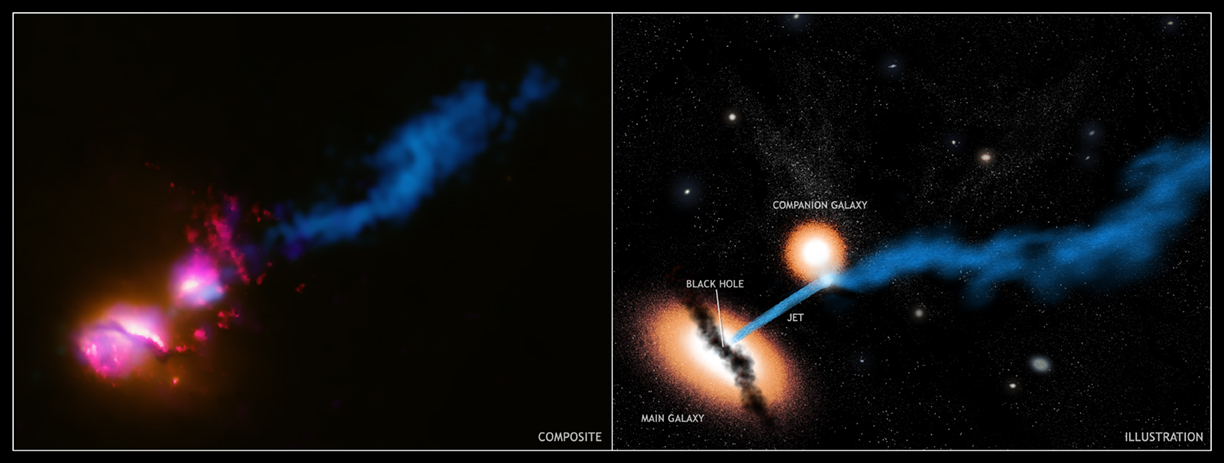

Death Ray

Death Ray