Where were we before our brief cultural meanderings? Right, we were looking at Beckett's Malone Dies—we cannot escape its orbit.

In Malone, we found traces of the lingering religious bias in literature in its assumption of a soul, something beyond thought, beyond physical suffering. Something that may or may not endure. No such religious atavism in Remainder, however. All traces of religious influence have been effaced, deferred, distanced; the most prominent occurring spectacularly at the end with the haunting, magisterial image of the plane flying a figure eight (the symbol for infinity), almost like a prayer, in the sky:

"I looked out of the window again. I felt really happy. We passed through a small cloud. The cloud, seen from the inside like this, was gritty, like spilled earth or dust flakes in a stairwell. Eventually the sun would set for ever—burn out, pop, extinguish—and the universe would run down like a Fisher Price toy whose spring has unwound to its very end. Then there'd be no more music, no more loops. Or maybe, before that, we'd just run out of fuel. For now, though, the clouds tilted and weightlessness set in once more as we banked, turning, heading back, again."Malone attempts to distanciate himself from his dying by telling stories, something he refers to as play:

"This time I know where I am going, it is no longer the ancient night, the recent night. No it is a game, I am going to play. I never knew how to play, till now. I longed to, but I knew it was impossible. And yet I often tried. I turned on all the lights, I took a good look all round, I began to play with what I saw. People and things ask nothing better than to play, certain animals too ... I shall never do anything any more from now on but play. No, I must not begin with an exaggeration. But I shall play a great part of the time from now on, the greater part, if I can. ... I must have thought about my time-table during the night. I think I shall be able to tell myself four stories, each on on a different theme. One about a man, another about a woman, a third about a thing and finally one about an animal, a bird probably." (180-81)There is some initial confusion in Malone Dies as to whether Malone is telling his stories verbally or writing them down with his nib of a pencil in his exercise book. Beckett doesn't really distinguish between the two, though he does indicate: "At first I did not write, I just said the thing. Then I forgot what I had said. A minimum of memory is indispensible, if one is to live really." (207)

The first story he tells involves the young Saposcat. As everyone knows, the name is a combination of Sapiens and scat, or "I know shit." [Macmann-'son of man'; Malone-'evil one'; Lambert-'unit of light'; Lemuel-'belonging to god'; Moll-'prostitute', nickname for Mary; blah, blah, blah]. This story-within-a-story feels like it might have been a story once written by the younger Beckett and wrangled into the context of Malone's telling. It is a traditionally realist story..."What tedium," interjects Malone into the telling. How telling!

"What tedium. And I call that playing. I wonder if I am not talking yet again about myself. Shall I be incapable, to the end, of lying on any other subject? I feel the old dark gathering, the solitude preparing, by which I know myself, and the call of that ignorance which might be noble and is mere poltroonery. Already I forget what I have said. That is not how to play...." (189)[Poltroon=coward] Even though it is his own story, Malone seems to have little control over it—at least ostensibly. He doesn't understand why Sapo isn't expelled from school for an infraction over a stick. This lends credence, in my mind at least, that this happened to Malone and he doesn't understand the grace or human kindness that spared him punishment for his sin: "I shall make him live as though he had been punished according to his deserts." (190) So, he treats Sapo as if he had been expelled. This feels like remorse by Malone, wishing he hadn't sinned—though it is quite opaque in the story how Sapo relates to Malone. Fact is, it doesn't matter, though it makes for fun speculation.

Beckett qua Malone continually interrupts and comments on the ordinariness of his story: "Sapo loved nature, took an interest This is awful." (191) Yet he continues with the story of Sapo/Macmann. Malone doesn't like his own writing. We are lead to ask whether this is Beckett commenting on his own writing style, or, more broadly, on traditional modes of storytelling. It is a good question. So, leave it to Beckett to answer his own question:

"We are getting on. Nothing is less like me than this patient, reasonable child, struggling all alone for years to shed a little light upon himself, avid of the least gleam, a stranger to the joys of darkness. Here truly is the air I needed, a lively tenuous air, far from the nourishing murk that is killing me. I shall never go back into this carcass except to find out its time." (193)How reliable is this comment? Who knows.

Throughout the novel, there is Beckett's trademark, marvelous humor. For example, the story about the Lambert's dead mule: "Together they dragged the mule by the legs to the edge of the hole and heaved it in, on its back. The forelegs, pointing towards heaven, projected above the level of the ground. Old Lambert banged them down with his spade." (212)

That's good, old-fashioned slapstick. Could've been in a Monty Python film.

Then there's Beckett's perverse side:

"When the meal was over Edmund went up to bed, so as to masturbate in peace and comfort before his sister joined him, for they shared the same room. Not that he was restrained by modesty, when his sister was there. Nor was she, when her brother was there. Their quarters were cramped, certain refinements were not possible. Edmund then went up to bed, for no particular reason. He would have gladly slept with his sister, the father too. I mean the father would have gladly slept with his daughter, the time was long past and gone when he would have gladly slept with his sister. But something held them back. And she did not seem eager. But she was still young. Incest then was in the air. Mrs. Lambert, the only member of the household who had no desire to sleep with anybody, saw it coming with indifference. ... What tedium." (215-16)This is classic, realist narrative with that perverse Beckettian twist. It extends the form, but does not [transcend] it. What tedium. It is not enough for the artist.

Neither is the naturalist, mimetic beauty of Beckett's prose:

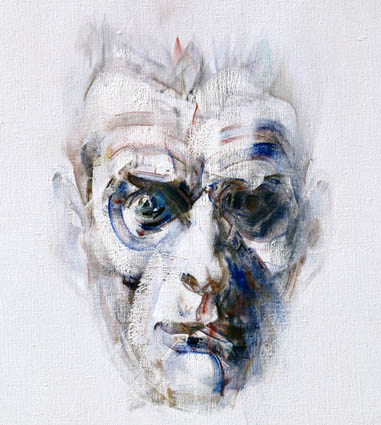

"Then Mrs. Lambert was alone in the kitchen. She sat down by the window and turned down the wick of the lamp, as she always did before blowing it out, for she did not like to blow out a lamp that was still hot. When she thought the chimney and shade had cooled sufficiently she got got [sic] up and blew down the chimney. She stood a moment irresolute, bowed forward with her hands on the table, before she sat down again. Her day of toil over, day dawned on other toils within her, on the crass tenacity of life and its diligent pains. Sitting, moving about, she bore them better than in bed. From the well of this unending weariness her sigh went up unendingly, for day when it was night, for night when it was day, and day and night, for the light she had been told about, and told she could never understand, because it was not like those she knew, not like the summer dawn she knew would come again, to her waiting in the kitchen, sitting up straight on the chair, or bowed down over the table, with little sleep, little rest, but more than in her bed. ... " (216-17)Such lyrical beauty; this could easily be the description of a still life by a Dutch master: the dying light, the posture, the face, the sadness. Yet, to Beckett qua Malone: "Mortal tedium." (217)

Still, tedious or not, writing is crucial to remembrance: Malone drops his pencil and cannot find it for forty-eight hours. "I have spent two unforgettable days," he tells us, "of which nothing will ever be known..." (222)

What is to be done? Malone reverts, as he promised, from storytelling to describing his 'present state'—a standard novelistic move. Malone, like Ivan Ilych, feels himself dying gradually, feels his body distancing itself from him:"

But this sensation of dilation is hard to resist. All strains towards the nearest deeps, and notably my feet, which even in the ordinary way are so much further from me than all the rest, from my head I mean, for that is where I am fled, my feet are leagues away. And to call them in, to be cleaned for example, would I think take me over a month, exclusive of the time required to locate them. Strange, I don't feel my feet any more, my feet feel nothing any more, and a mercy it is. And yet I feel they are beyond the range of the most powerful telescope. Is that what is known as having a foot in the grave? And similarly for the rest. For a mere local phenomenon is something I would not have noticed, having been nothing but a series or rather a succession of local phenomena all my life, without any result. But my fingers too write in other latitudes and the air that breathes through my pages and turns them without my knowing, when I doze off, so that the subject falls far from the verb and the object lands somewhere in the void, is not the air of this second-last abode, and a mercy it is." (234)Frantically, Malone reverts to storytelling: There is some wallowing and squirming in the mud. There are possessions, lost, found, and lost. There is a hat on Macmann and one on an ass. There are sticks and bloody clubs. And Macmann comes/goes to the asylum. There is sex with his keeper, Moll. There is a tooth carved in the shape of a crucifix. There is murderous rage and a murder. There is the theft of bacon from the 'excursion soup' by the unscrupulous keeper, Lemuel. And there is the inmates' murderous excursion to the island with the asylum's benefactor, Lady Pedal.

Then, again, Malone's dying:

"A few lines to remind me that I too subsist. He has not come back. How long ago is it now? I don't know. Long. And I? Indubitably going, that's all that matters. Whence this assurance? Try and think. I can't. Grandiose suffering. I am swelling. What if I should burst? The ceiling rises and falls, rises and falls, rhythmically, as when I was a foetus. Also to be mentioned a noise of rushing water, phenomenon mutatis mutandis perhaps analogous to that of the mirage, in the desert. The window. I shall not see it again. Why? Because, to my grief, I cannot turn my head. Leaden light again, thick, eddying riddled with little tunnels through to brightness, perhaps I should say air, sucking air. All is ready. Except me. I am being given, if I may venture the expression, birth to into death, such is my impression. The feet are clear already, of the great cunt of existence. Favourable presentation I trust. My head will be the last to die. Haul in your hands. I can't. The render rent. My story ended I'll be living yet. Promising lag. That is the end of me. I shall say no more." (283)Malone fails at his projects. He does not complete his stories—and what he completes is tedium, mortal tedium—though he scribbles furiously and unconsciously. His possessions seem to take on a life of their own, refusing inventory, wandering off, returning mysteriously. And his present state, well his present state dwindles into a homunculus inside his head and, after the rest of his body, is extinguished into a terrible darkness.

Such is Beckett's stark vision of the inner life of the dying Malone. Trying to avoid himself, he finds himself. Trying to escape his fate, he dies. We watch him, in that most memorable phrase, "being given...birth to into death."

In terms of the Ur-story theme we've been pursuing, Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilych was pure porn, a literary snuff piece, if you will, much like Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ was pretty much a pornographic, snuff film: the level of the storytelling is intense, direct, realistic; trapped within its own form. Beckett tries to escape the ambit of 19th Century realism by commenting—derisively we might add—on his own storytelling. In the face of the Ur-story, Beckett seems to be showing us, straight-on storytelling simply will not suffice. Tom McCarthy has absorbed this lesson. Remainder (and with it, Synecdoche, New York) is, indeed, the child of Malone Dies.

No comments:

Post a Comment