[continued from previous post]

[continued from previous post]Much has been made of the use by Vladimir Nabokov ['VN'] (the dead writer, married to Vera, father of Dmitri, teacher of Thomas Pynchon at Cornell) of mirror subjects, or doppelgangers. In Pnin, he employs one Vladimir Vladimirovich ['VV'] who, it must be remarked (because it has so often been), bears considerable affinity with VN, to narrate the rather simple, sentimental story of Pnin. VV is a fictional character who is something like VN—but not to be identified with him. The details of VN's life and their similarity with those of VV are not at all relevant here. Nor is the question of who was the real-life model for Pnin—though much ink has been spilled doing precisely this. We are more concerned about how Pnin works.

VV, the narrator, presents Pnin as a compelling, sympathetic character whose story, though slightly comic, is relatively simple and uncomplicated: Pnin, 57 year old untenured professor of Russian at a small liberal arts college in upstate New York, takes wrong trains because he uses out-of-date schedules. The idioms and nuances of English, his second or third language, confound him. He is absent-minded and myopic. He has heart seizures that send him into reveries about his past. He moves from rooming house to rooming house practically each semester. He lectures to his classes from printed texts, rarely looking up to acknowledge his students. He puts calls on library books he has already checked out (and which nobody else on the campus could possibly want). He has all his teeth pulled and enjoys the improvement. He is genial. He makes a near-heroic effort to adjust his old world manners to new world customs. He is an old school scholar (running down endless strings of obscure footnotes) in a pragmatic, career-oriented education system. He misses his ex-wife, the feckless Liza (with whom, we are led to believe, VV had an affair), and wants desperately to connect with her teenaged son, Victor—an incipient artist. Pnin is a former social acquaintance of VV. He, like many in his rootless, emigre community, is nostalgic about pre-civil war, Czarist Russia. He enjoys brief, cooling swims in summer. He is a gracious, generous host. He loses his job at Waindell College when his benefactor, Hagen, takes a better position at another college.

"[Y]ou'll be glad to know that the English Department is inviting one of your most brilliant compatriots, a really fascinating lecturer—I have heard him once; I think he's an old friend of yours."We also learn along the way that Pnin was separated from his former youthful crush, one Mira Belochkin, by the Russian civil war and revolution. She, a Jew, was slaughtered at Buchenwald.

Pnin cleared his throat and asked.

"It signifies that they are firing me?"

"Now, don't take it too hard, Timofey. I'm sure your old friend—"

"Who is old friend?" queried Pnin, slitting his eyes.

Hagen named the fascinating lecturer.

Leaning forward, his elbows propped on his knees, clasping and unclasping his hands, Pnin said:

"Yes, I know him thirty years or more. We are friends, but there is one thing perfectly certain. I will never work under him." (169-70)

What do we know about VV, then? For all intents and purposes, Pnin disappears at the end of Chapter 6, and VV steps forward and takes over Chapter 7 to justify his narrative: "My first recollection of Timofey Pnin is connected with a speck of coal dust that entered my left eye on a spring Sunday in 1911." (174) He claims to have met Pnin socially a couple of times in and around old St. Petersburgh, though Pnin refutes this. As ex-pats, they met again in Paris. There, VV also met Liza, an incipient poet. She sends VV her poems. He tells her they are bad and she should stop composing. Later, VV reviews them in her room—"the cheapest room of a decadent little hotel"—and, apparently, they have a brief, torrid affair: "In the result of emotions and in the course of events, the narration of which would be of no public interest whatsoever, Liza swallowed a handful of sleeping pills." (181-82). A few weeks after that incident, Liza importunes VV for his advice on a rather pedantic marriage proposal by Pnin. She tells him: "I shall wait till midnight. If I don't hear from you, I shall accept it." (182) He shuns her seemingly desperate plea, and she marries Pnin. VV, it seems, is a bit of a cad. Later, Liza "told Timofey everything," and he pardoned her. (184) VV meets Pnin some years later, and Pnin insults him: "Now, don't believe a word he says... . He makes up everything. ... He is a dreadful inventor." (185) In the forties, VV and Pnin (now divorced from Liza) meet in New York, and all seems to have been forgotten. Later, VV accepts the English Department position at Waindell and, indeed, offers Pnin a job:

"When I decided to accept a professorship at Waindell, I stipulated that I could invite whomever I wanted for teaching in the special Russian Division I planned to inaugurate. With this confirmed, I wrote to Timofey Pnin offering him in the most cordial terms I could muster to assist me in any way and to any extent he desired. His answer surprised me and hurt me. Curtly he wrote that he was through with teaching and would not even bother to wait till the end of the spring term." (186)When VV arrives at Waindell, after an evening of lampooning Pnin with another colleague, he crank calls Pnin and, the next morning, stalks him as he's leaving town. That is the last we see of Pnin and his dog, and that is the end of the book.

The two men have a long and complicated history. Both remember fondly their pre-war days in Czarist Russia. VV seems to have adapted to the American ways and language, while Pnin still retains his Old World manners. VV seems to have been more successful ("brilliant", "fascinating lecturer") as well. And then there's the matter of the woman. Yet, this does not explain why VN needed to interject VV into the narrative to tell the story of Pnin.

Or, to frame the question another way: Why does VN need to use this so-called post-modern technique? What purpose does it serve? Stylistic devices, it seems to me, need to have some rationale. It's like the twenty-minute drum solo in Iron Butterfly's "In-a-gadda-da-vida": sure, it's long and technically show-offy, but how does it contribute to the song? Is VN merely being self-indulgent, here? Showing off? Let's look:

We know VV is not entirely reliable. As I pointed out in the last post, he relates things he cannot possibly know. Even Pnin knows this ("He makes everything up.") And to drive the point home, we are told in the last paragraph of the book that VV is being told "the story of Pnin rising to address the Cremona Women's Club and discovering he had brought the wrong lecture." (191) Of course, we recall that the first chapter is about Pnin taking the wrong train to Cremona where, as he is about to rise to deliver his lecture, he has a vision about the past (including his parents, an aunt, a friend killed by "the Reds", and "shyly smiling, sleek dark head inclined, gentle brown gaze shining up at Pnin from under velvet eyebrows, sat a dead sweetheart of his, fanning herself with a Program. Murdered, forgotten, unrevenged, incorrupt, immortal..." (p.27) Of course, this is Mira.).

Pnin is, at first face, a comical character, often the butt of jokes and lampoonings on campus. This is the way the world—especially the American world—sees him. VV invents stories about Pnin's inner life that show Pnin's endearing side. He shows Pnin's pain (as, e.g., about Mira); his pride (as, e.g., his proposal and dignified commitment to faithless Liza); his poignancy (as, e.g., when he connects with Victor, tosses out the soccer ball he'd bought for him when he realizes it would be inappropriate, and receives as a trophy a beautiful punch bowl which he nearly breaks in one of the few really suspenseful moments in the book); his passion (as, e.g., for the arcana of Russian culture). This takes an act of the imagination, and however unreliable it might be, is, perhaps, the only way one human can come to empathize with another. And, VN seems to be showing us, it is the lack of precisely this sort of sympathetic imagination that resulted in the unfathomable horrors that defaced the 20th Century:

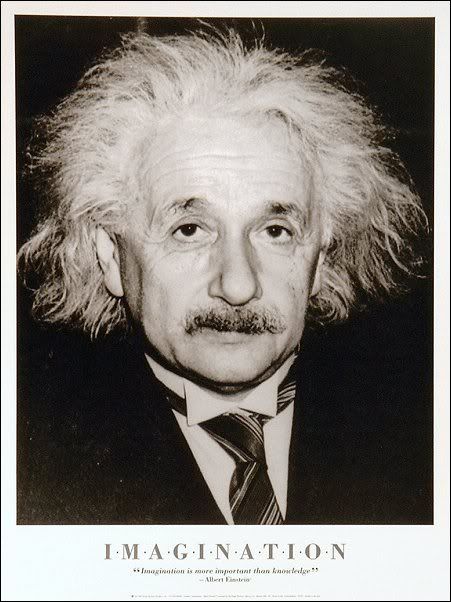

"In order to exist rationally, Pnin had taught himself, during the last ten years, never to remember Mira Belochkin—not because, in itself, the evocation of a youthful love affair, banal and brief, threatened his peace of mind (alas, recollections of his marriage to Liza were imperious enough to crowd out any former romance), but because, if one were quite sincere with oneself, no conscience, and hence no consicousness, could be expected to subsist in a world where such things as Mira's death were possible." (134-35)Art and literature—i.e., The Imagination—are the best we have for overcoming our aloneness and our alienation, for transcending our own egos and entering into the experience of another.

According to James Wood, in How Fiction Works, "the history of the novel can be told as the development of free indirect style." In this regard, he cites Pnin and shows how Nabokov sort of backs into a kind of FIS almost by accident in Wood's close reading of the book's description of a nutcracker as "the leggy thing." ("Nabokov is here using a kind of free indirect style, probably without even thinking about it." Section 20). Wood, here, misses the impact of VN's having VV mediate the narrative of Pnin's interiority. It doesn't matter whether VN gets out of the way and gets Pnin's words right. The unreliability of the narrator is key here—it means something—because VV is attempting something quite impossible: sympathetically imagining and portraying another person's thoughts and memories, entering the experience of another. He's going to get it wrong. [I'm planning a subsequent post comparing the free indirect style and the writer's notion of 'voice'.]

Pnin is mediated by VV's narrative, and VV is imagining another being, another mind. It doesn't matter if VN gets the language of Pnin right because we know VV doesn't (and can't) get it right. Here, in a very real way, VN's style is precisely the substance. VN is more of a master of the free indirect style than Wood can see. That is to say, Wood is just plain wrong here: VN employs the free indirect style to bring us the character of VV vainly trying to imagine the inner world of Pnin! [One thinks of such cliches as nesting Russian dolls, and 'riddle[s] wrapped in [m]ysteries inside enigmas'.] Wood is right only to the extent that VV's (not VN's) use of 'thing' represents a success at imagining the inner life of Pnin. VN is entirely successful at representing the language and thought of VV (which Wood utterly fails to see).

VV is necessary thus. It is his effort—the supreme spiritual effort, if you will, of attempting to imagine and understand and empathize with another person's interiority—that matters. And, for the record, it has nothing to do with faith or dogmatism.

The muddle's the thing.

5 comments:

Jim,

I know I'm risking our nascent friendship by telling you this, but since you revealed your loss of your best friend from post 9/11 injuries, I cannot help reading every word you write through that lens. I honestly believe it is now time for you to bring your gifts to bear on that difficult, no doubt excruciatingly painful but essential, subject. Avoidance is a form of smoke at this point, and this carping at poor James Wood, who is, after all, doing the very best he can under tremendous scrutiny and pressure, is somewhat besides the point in my view.

You always ask, what's it all for? Show us, Jim. Show us what a writer you are, how you can--to paraphrase a mutual friend-- constitute her through your writer's determination to invoke her in your words, and thus render her also wholly real. You're doing it anyway. I can practically see her and she's amazing. I would have liked to have known her and have had the chance to befriend her. Please Jim, make a proper introduction.

FM,

I do appreciate your thought. The way I think of it, this isn't really that kind of blog. I don't think of this as a personal diary. I have a friend who does that (and does it well), but I'm not such an interesting personality.

As for fictionalizing family and friends or even myself (something VN has done to profound effect), don't worry, I have drafts and drafts of stories incorporating aspects of people I've known as characters. And they are beginning to circulate.

Best,

Jim H.

Not having read Pnin or How Fiction Works (though both are now on my reading list), it was difficult for me to understand how Wood could have interpreted the description of a nutcracker as "the leggy thing" as Nabokov's backing into free indirect style - but I Googled it and see just what you mean (inclusion of the passage from How Fiction Works would be illuminating for the unexposed reader).

But that's nothing.

Your reading was really quite amazing. The rationalization of VV's fabrication of details to which he couldn't not have been privy - it reminded me of the people-watching I do on trains, inventing the destinations and origins of complete strangers - making them *real*. And of advice given in the case of a hostage situation: share details of your life and family with your captors, transforming yourself from a victim and into a human being.

Great post!

You've definitely won a new reader.

Me again. Okay, I found the rest of your blog (!) Great post, again. I am writing a novel at the moment and this really helps clarify some of the issues I'm dealing with. Many thanks!

I agree with you about Franzen too (in your Gaddis posts).

Post a Comment