Some Principles of Narrative Theory:

- A1. The work of fictional narrative is to modulate an event or sequence of events into a scene or scenes. (Genette)

- A2. A character is a linguistic construction representing a person whose actions are in some wise important: The metaphor systems used to depict a character reveals certain things about that character, conceals others, and implies still other illusory qualities about that character. (Lakoff)

- A3. The time, or pace, of a narrative is a function of the relation of the length of a scene to the duration of the event it depicts, where (ideally) straight dialogue bears a one-to-one relationship ("isochrony", real time = 'showing') to the time of an actual conversation. (Genette) Corollary: it is important to vary the pace of scenes; this is also known as rhythm.

- A4. Narrative (fictional or non-) is essential to understanding events. (DeCerteau)

- A5. In narrative, historical scenes need not be presented chronologically; this has been called "achrony". (Genette) Corollary: no historical time need pass during a scene.

- B1-13. The realist story is a product [even a commodity] in today's culture. Through its effects, Its production, however, can be examined and, in point of fact, is structurally and syntactically quite similar to the sentence, or the posing of a question and its subsequent resolution. (Barthes)

- C1. With respect to point of view, there really is not that much substantive difference between 'quoted monologue' (a/k/a omniscient: '"I am late," he thought'), 'narrated monologue" (a/k/a free indirect:: 'He was late.'), and psycho-narration (a/k/a limited omniscient 'He knew he would be late.'). "Narrated monologue represents, in the third person, the exact thoughts of a character who is narrated in the third person," and, out of context, is indistinguishable from straight narration. (49) (Cohn)

- C2. The real author and the real reader are irrelevant to the narrative. Yet, the implied author and the implied reader, important as they are, are distinct from the true voice of the narrative: the narrator, whose values (as, e.g., to truth and reliability) differ significantly from the implied author and who addresses a narratee (either identified or implied). Point of view, then, can be formulated as "access by a narrator (who could be a character) to historical information (events in the story) and thoughts of other characters and even their own)." (57) (Chatman)

- C3. A brief anatomy of types of narrator:

"1. An external observer who narrates actions and dialogue. (camera, fly-on-the-wall)

2. An internal observer capable of narrating the characters' conscious thoughts.

3. An external omniscient narrator who knows things about the history the characters do not.

4. An internal omniscient narrator capable [sic] who knows the characters' unconscious motivations." (57)

- C4. Sensory input is the basic unit of human experience. No narration can adequately show this. There are only degrees of and kinds of telling, more or less detailed, more or less vivid.

- C5. Like metaphor systems (A2), narratives are important tools for understanding complicated social and historical situations, revealing and concealing aspects of life at the same time as they create certain illusions. (Lakoff)

- C6. The narrator stands in one of three relations to the character: he knows/says more than any of the characters knows/says, he knows/says as much, he knows/says less. Similarly, the narrator stands in the same set of knowledge relations to the reader. (Todorov)

- C7. [This section is like the scene in Woody Allen's Annie Hall in which a scene of dialogue is accompanied by subtitles showing what the characters were actually thinking.]

- C8. The author's choice of person (first, second, or third), singular or plural, does not significantly limit what it is possible to narrate. (Reagan, et al.)

- D1. Female characters in male, realist fiction are often used merely, or mostly, either to provide a sexy background or otherwise motivate or constrain the central male characters. (Chynoweth)

- D2. Yet, it is possible to have a narrative without a character (male or female), or, rather, without the illusion of the character's presence. [One thinks, here, of Tyrone Slothrop's disappearance two-thirds of the way through the narrative of Gravity's Rainbow. We still feel the effects of his having been 'present', or having just missed him, etc.]

You can find these principles discussed in fuller detail in William Gillespie's short book The Story That Teaches You How To Write It.

The text consists of explanatory essays on each of these topics on the recto pages of the book, while on the verso pages we find the narration of a story that putatively puts each of these theoretical points into play. Along with this, there are footnotes throughout claiming to be critical comments on the story and essays from participants in the author's graduate creative writing seminar—for which this was his final project. At the end, there is a bibliography, a letter from 'William' to someone named Dave, and, on the back there is a letter to 'William' from someone named Ben.

The story itself concerns two lesbian grad students (one brilliant, the other struggling) in a theory-oriented, creative writing program, and the affair one of them has with their married, male professor.

The author states his purpose as follows: "My attempts to translate narrative theory into instructions on how to write a story are part of a larger process of turning the world into instructions on how to write a story." (3) A noble, ambitious aim, comprehensive and well-stated.

Gillespie claims to have been a student in one of David Foster Wallace's seminars, and this book even includes some critical commentary from a 'DFW', as well as a letter to 'Dave'. At face value, it appears to be a fairly literalistic attempt to apply narrative theory to fictional praxis (as grad students are presumably instructed to attempt to do): theory is stated, indexed (A1., A2., etc., as above), and seemingly applied to correspondingly numbered segments of narrative. Thus, we are called upon to read the pieces as separate: a) story and b) theoretical essays. As such, it is the story that also tries to teach us how to read it. But the attempt feels mechanical and heavy-handed: rote and clunky. And, frankly, we don't have to obey.

A struggling English grad student writing a story about a struggling English grad student writing a story should be our first clue that something else is going on here. Identities are at stake. Per C2 above, the real author is irrelevant; let's leave him be for now. So we follow the chain down: implied author —> narrator. The 'Gillespie' who has penned these essays on theory and the love-triangle story about creative writing grad students (the narrator) should not be equated with the Gillespie who apparently lives in Illlinois and has written this book (about a narrator/character named 'William Gillespie') and who appears to have a Web presence here. But neither should he be confused with the 'William Gillespie' who is the implied author of this text, including the prefatory material, the footnotes, bibliography, and assorted interjections here and there.

The narrator tells us he has written some essays on narrative theory and attempted to apply them to his fiction writing. As such, the work is divided. It's kind of stale and dry, an interesting intellectual exercise. But nothing, as they say, to write home about.

One feels there must be something more, some unifying principle that brings the disparate materials of this pastiche of a book together. That, we learn, is the role of the implied author. (C2) If there is an implied author who provides some overarching unity to this seemingly divided book, it must be the 'Gillespie' who has created the 'Gillespie' narrator/character. The implied author of the grand, totalizing narrative knows more than the narrator/character. (C6) The narrator 'Gillespie' has composed both the story and the essays and claims to have fit the square peg of theory into the circle of practice. 'Gillespie' the implied author recognizes this as a delusion.

At the end, in a letter putatively penned by this implied author 'Gillespie' to DFW, we read:

"I seem to have written myself back into a corner of my own brain so remote that not even you and Jason and a team of English graduate students working together with searchlights, helicopters, and bloodhounds, can find me. My writing has improved so much since I entered graduate school that there is no longer anyone qualified to read it." (78)It is a difficult matter to untangle. 'William Gillespie' (narrator) claims to be the master of theory and claims to have successfully applied all these grad school tools to his narrative. Story prevails, absorbing all theory into the black hole of its narrative flow. 'William Gillespie' (implied author), on the other hand, claims to be a singular genius who has included all these theoretical essays in the book so he can justify his story's shortcomings to his classroom critics:

"In class for the first time I received more sadness than hostility: a room full of blank faces, letters which read like page-long apologies, and meanwhile Jason accusing me of misrepresenting theories I wasn't, in many cases, even trying to represent. I've seldom gone to so much trouble to do such a small segment of a possible readership so little good. ... I started writing like this, in fact, because of a workshop. I needed decision-making criteria so that, when I received a flood of individually contradictory but collectively discouraging instructions about what to change, I would have the original structure as a guide to know which advice I could use and which I couldn't." (78)Contempt, confusion, hurt, resentment, anger, perhaps even madness. These are the words of a sensitive soul who has been beat up once too many times in a writing workshop, someone who took it all too personally and is lashing out the only way he can: "Nobody understands me!" This 'William Gillespie' does not appear in the text of the story (D2) except, perhaps, in drag (D1) and multiply (C8), and is specifically concealed behind the illusion of the in-control, imperious theory master (C5, C6) like a Bunraku puppeteer. (C3)

What raises this seemingly dry theory-exercise to the level of Ur-story is the re-visioning of the narrative necessitated by 'William's' letter to 'Dave':

"Dave, Class last week brought up a number of interesting questions. Questions like what the hell am I doing with my life? ... After working on the paper it occurred to me that I actually know what the hell I'm doing. I know exactly what I'm doing. I'm going broke and insane trying to teach the English language to dance." (78) 'William' ("P.S. Please stop calling me 'Bill.'") is self-aware enough to recognize that he is an uninspired "blocked writer" who, paradoxically, must yet strive to "constrain the impassioned diuretic flow of cliches in [a] confident writer[]." (78) The experience of loss—loss of inspiration, loss of focus, loss of girlfriend(?) (C8, D1), loss of time, loss of ideals, loss of faith in humanity, loss of faith in himself and his ability to understand his world, and a near-Nietzschean loss of sanity—the experience of loss permeates this book.

Whereas 'Gillespie' the narrator is vain and cocky, 'Gillespie' the implied author is pathetic and insecure.

The Story That Teaches You How To Write It is a complex, disjointed "model of consciousness." 'William Gillespie', the implied author (not necessarily the "real author" (C2)), is a brilliant, but very nearly unhinged character attempting to find some creative grounding for the ungainly welter of theoretical dicta that have been plaguing his mind for nearly a decade. This book represents his life's work (B1-13), and it is a failure—though an interesting and ambitious one. This makes him, and his story, compelling—especially to someone (such as, ahem, yours truly) whose ambitions and failures find remarkable resonance in this short, powerful effort of the spirit.

----------------------

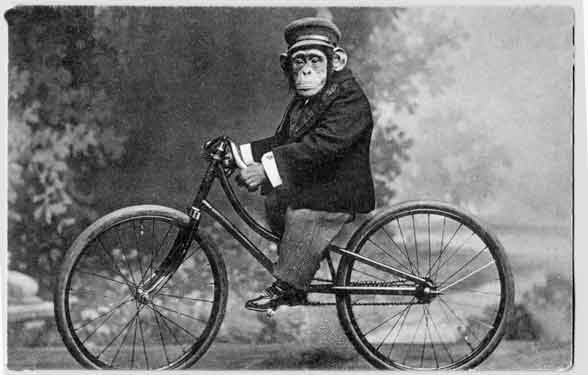

A quote from the letter on the back of the book, which Gillespie refers to as a "preface" (77), inspired me to revive one of my favorite pictures from a previous post on my blog for this post:

"I am the Eskimo watching the basketball game. Except I'm more like an Eskimo who thinks he's watching a basketball game, but isn't really sure because he doesn't really know what basketball is, so he may not be watching a game at all. My relationship with literary theory; most theory, hell any theory, is like a monkey riding a bicycle. He can do it; the monkey, he can ride the bike if he tries hard enough. But he never looks or feels comfortable doing it. It's possible; it's been done, but it sure as hell isn't pretty."