I am baffled. Everywhere I turn, it seems, I read or hear some opinionated commentator either attacking or defending President Obama's nomination of Judge Sonia Sotomayor for the upcoming vacancy on the United States Supreme Court.

I am baffled. Everywhere I turn, it seems, I read or hear some opinionated commentator either attacking or defending President Obama's nomination of Judge Sonia Sotomayor for the upcoming vacancy on the United States Supreme Court.The degree of abject ignorance on the issue of what a judge does and what, beyond that, an appellate judge does is astounding. What's more, even seemingly bright people who should know better resort to canned, irrelevant arguments. They have formed their opinions before all the facts are in. Their feelings lead.

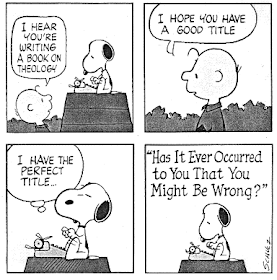

This is precisely the opposite of how a judicial opinion is formed. These knee-jerk commentators, however, assume that because that's how they work (they form their opinions based on how they feel about things [politics, culture, self-interest, etc.] and then argue based on their beliefs—ignoring or misconstruing facts that provide counter-examples to their opinions) they assume that because that's how they operate that's how judges work, how they decide cases. This is another species (the political variety) of the obstinate ignorance I blogged about just below.

I recall a series of questions on the LSAT about credibility. They went something like this:

Obviously, this is only an approximation of the type of question, but it is illustrative. The point is: there are relative degrees of credibility.Who is more credible?

- a conservative plumber expounding on the debt financing crisis of the 21st Century;

- a liberal clergy person explaining particle physics and String Theory;

- a lesbian chemist discussing theories of moral reasoning;

- a spokesman for the oil industry arguing against proposed environmental regulations;

- a famous actor who plays a doctor on TV asking you to purchase a certain medication;

- a white journalist tracing the effects on former slaves of Reconstruction legal decisions; or

- a Mexican historian describing the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam among Lee's generals.

People who might really know how to read and critique a poem or a novel, or how to launch an effective PR campaign, or how to attack liberal politicians on TV are taking sides on the Sotomayor nomination—mostly attacking her. She used such-and-such words in a speech ten years ago. She is ethnic, maybe even Mexican. She belonged to some community group I know nothing about. She is a woman. She has a funny name. She eats funny foods. She is not like me. She is empathetic.

It's preposterous. Plain and simple: None of these flacks knows how to read a judicial or appellate opinion. They have no concept of legal reasoning. They have never tried to extract a rule or principle of law from a diverse or even contradictory set of cases. They don't know how a set of facts is properly established in a trial setting. They couldn't apply a statute or rule or even an established legal principle to a complex fact pattern, much less decide between applicable but conflicting legal or statutory or statutory or Constitutional priorities. They have not critically read all the historical decisions of the Supreme Court on any given Constitutional issue. Nor, most likely, has any of them clerked for Judge Sotomayor or argued before her or observed her courtroom manner or read all of her opinions (including the arguments that were before her).

Yet they are attacking her.

I personally have never argued before Judge Sotomayor, though I have prepared briefs for senior lawyers who have. I have read any number of her opinions (often in preparation for writing just such a brief so I could see what sort of arguments she found persuasive). However, I simply don't have an opinion about her fitness for the Court. As I indicated in my previous post, this is why I could never be a pundit or a TV talking head. I don't form knee-jerk opinions based on my own predispositions or political predilections.

It's preposterous. Plain and simple: None of these flacks knows how to read a judicial or appellate opinion. They have no concept of legal reasoning. They have never tried to extract a rule or principle of law from a diverse or even contradictory set of cases. They don't know how a set of facts is properly established in a trial setting. They couldn't apply a statute or rule or even an established legal principle to a complex fact pattern, much less decide between applicable but conflicting legal or statutory or statutory or Constitutional priorities. They have not critically read all the historical decisions of the Supreme Court on any given Constitutional issue. Nor, most likely, has any of them clerked for Judge Sotomayor or argued before her or observed her courtroom manner or read all of her opinions (including the arguments that were before her).

Yet they are attacking her.

I personally have never argued before Judge Sotomayor, though I have prepared briefs for senior lawyers who have. I have read any number of her opinions (often in preparation for writing just such a brief so I could see what sort of arguments she found persuasive). However, I simply don't have an opinion about her fitness for the Court. As I indicated in my previous post, this is why I could never be a pundit or a TV talking head. I don't form knee-jerk opinions based on my own predispositions or political predilections.

I suspect, however, because President Obama was famously a professor of Constitutional Law at one of the premier law schools in this country, that he has a sense of the caliber of her judicial mind. (I could never give the MBA president the same benefit of the doubt for reasons I've articulated a number of times in this blog. His picks were more overtly political in nature [think Harriet Myers], I felt. He wanted certain outcomes from his picks. Obama, if I read him right, is more interested in the process and the legal reasoning than the outcomes—which, to the uninitiated is the heart and soul of the law! Something they can never quite comprehend.)

Eventually, some commentators will appear who've made the effort to read all, or at least most of, her decisions. There will be attorneys who've argued before her—winners and losers. There will be her colleagues from the Southern District of New York and on the 2d Circuit Court of Appeals (arguably the pre-eminent such court in the country) who may or may not have something to say about the way she has dealt with them on the panels and en banc, who understand how she approaches the decision-making process. It is important to listen to such arguably quite credible sources—especially the winners who are against her and the losers who are for her and don't have some sort of political axe to grind. Read some of her opinions (you can find many of them on line). Listen to the Senate hearings. Take all points of view into consideration. Try to understand the rationales of both sides. Assess their relative credibility. Judge for yourself.

Just recognize, a judicial opinion is not like "I like Coke better than Pepsi" or "I pull for the Tar Heels" or "I always vote Republican" or "I hate Winnipeg." It's a lot more complicated and involves a process in which both sides on any given issue have had an opportunity to give it their best shot in an adversarial proceeding; and the judge has taken their relative contributions into consideration, weighed the arguments against the appropriate legal standards, and rendered a decision with the sort of legal reasoning that can be applied again and again (except, of course, in cases like Bush v. Gore, but that's a post for another day). And those who don't know this or don't understand this or refuse to acknowledge this—they are simply not credible, no matter how loud they shout or blog or Tweet.

Ignorance of the law is no excuse.

------------------

Btw: If you're interested, here's an essay by George Lakoff concerning that whole "empathy" matter. I've posted plenty about agápē and Max Scheler and humanism and the (un-)wisdom of crowds, among other things, if you want to know my own view.

Eventually, some commentators will appear who've made the effort to read all, or at least most of, her decisions. There will be attorneys who've argued before her—winners and losers. There will be her colleagues from the Southern District of New York and on the 2d Circuit Court of Appeals (arguably the pre-eminent such court in the country) who may or may not have something to say about the way she has dealt with them on the panels and en banc, who understand how she approaches the decision-making process. It is important to listen to such arguably quite credible sources—especially the winners who are against her and the losers who are for her and don't have some sort of political axe to grind. Read some of her opinions (you can find many of them on line). Listen to the Senate hearings. Take all points of view into consideration. Try to understand the rationales of both sides. Assess their relative credibility. Judge for yourself.

Just recognize, a judicial opinion is not like "I like Coke better than Pepsi" or "I pull for the Tar Heels" or "I always vote Republican" or "I hate Winnipeg." It's a lot more complicated and involves a process in which both sides on any given issue have had an opportunity to give it their best shot in an adversarial proceeding; and the judge has taken their relative contributions into consideration, weighed the arguments against the appropriate legal standards, and rendered a decision with the sort of legal reasoning that can be applied again and again (except, of course, in cases like Bush v. Gore, but that's a post for another day). And those who don't know this or don't understand this or refuse to acknowledge this—they are simply not credible, no matter how loud they shout or blog or Tweet.

Ignorance of the law is no excuse.

------------------

Btw: If you're interested, here's an essay by George Lakoff concerning that whole "empathy" matter. I've posted plenty about agápē and Max Scheler and humanism and the (un-)wisdom of crowds, among other things, if you want to know my own view.

------------------

UPDATE: Here's a great piece by another of my favorites, Stanley Fish, on this issue. Sorry I missed it the first time around. He makes the distinction between a decision that seems to be technically legally correct and yet seems unjust and one that is just but doesn't necessarily appear to follow the legal precedents strictly. On the surface, this is a valid distinction. But at the time many of the law review articles he cites were written, there simply weren't that many precedents to draw on. Since, say 1984, we've witnessed an explosion of case law of almost geometric proportions. Frankly, any good judge can find a precedent or even a thread of legal reasoning that conforms with his notion of justice; you just have to know how to frame the issue and do your research. What's more, a really good judge looks at all the precedents and then attempts to derive sound principles from them, especially where there are conflicting rulings—asking: what principle are these rulings attempting to inculcate?—and then applies the principle (not the strict legal precedent) to the case at hand. Harmonizing conflicting or even hostile legal rulings thus is a high-powered legal skill. Having a sound, consistent, and coherent set of principles and knowing how they apply and, importantly, when to apply them is the mark a great legal mind. And this, as I've argued above, is quite different from simply having a knee-jerk political reaction ("I'm pro-business", "I'm anti-abortion", "I'm anti-gun control", "I'm pro-States Rights"—that's you, Justice Thomas) and basing one's decisions on one's predilections or interests.